Leaps of faith

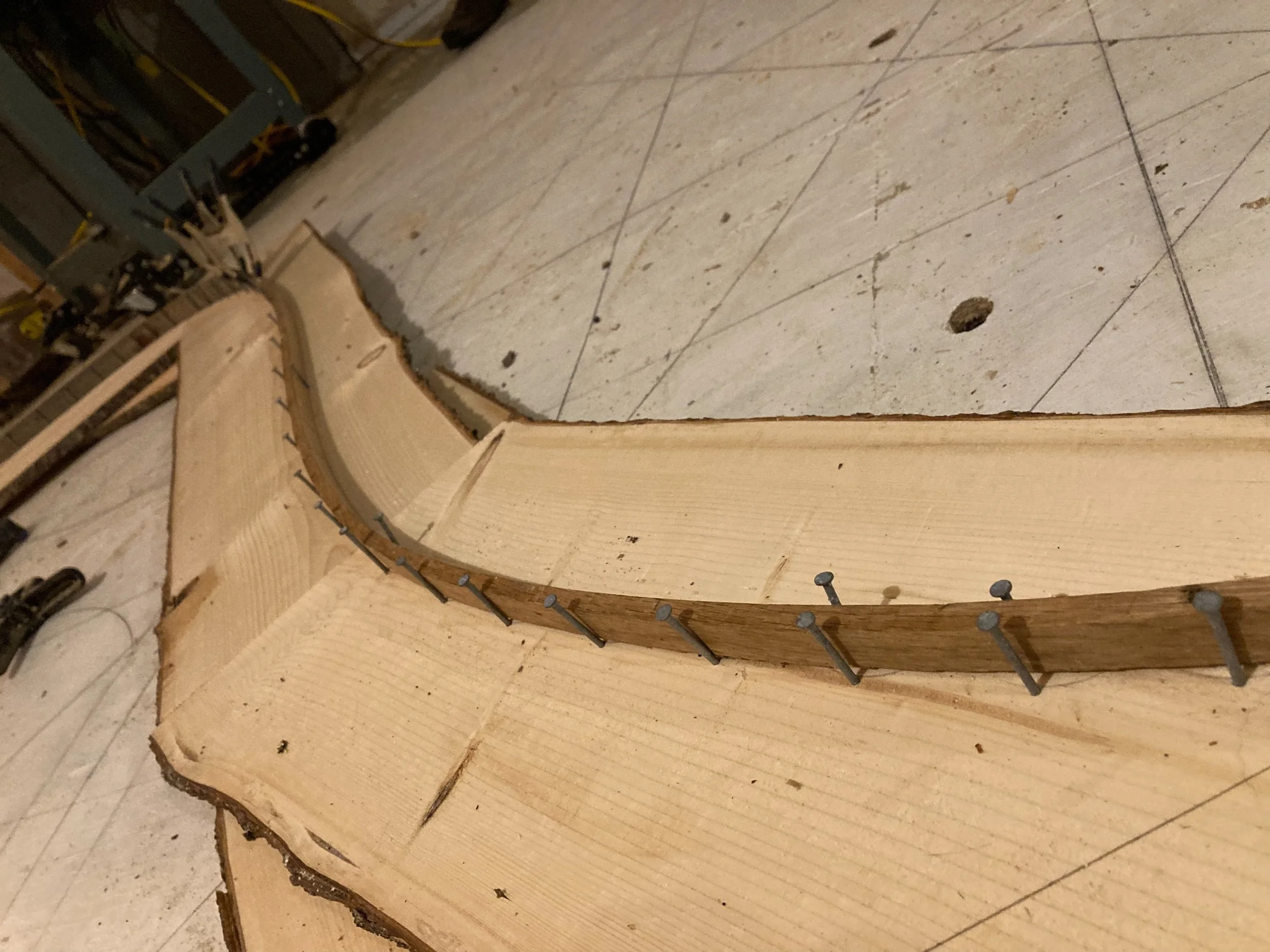

Sawyer removing nails after the line has been marked on a mold.

The molds are done!

At least, for the love of an oft bewildering God I hope they are.

I won’t know for certain until I lay the keel, raise the stem, build the tail feather, erect the molds at even spaces of 28 inches apart along her length and run battens around the works.

It’s only then, if all those battens curve true and fair for the 29 feet from stem to stern, that I’ll know whether my every spare evenings for the past three months have been a bust.

It wouldn’t be the first time I’ve wasted.

Nor, I hope, the last.

A fair curve is a marvelous thing and one boat building relies upon.

Our minds are as tuned to see them as they are to the musical scales.

A foul line will catch an eye as quickly as the cat will run from the room when I open my mouth to sing.

I remember standing on a fishing stage in Englee near Newfoundland’s northern tip as a home built 65 footer came through the harbour mouth. The fishermen on the stage turned their backs to the boat as it approached as if it were insult to something they hold dear about themselves.

“Looks like a God-damn milk crate,” one of them muttered.

I hope not to build a God-damn milk crate.

In wooden boat building as in life most your efforts are a leap of faith the uncertain results of which will reveal themselves in time.

The problem is when the crucible of this leap is your own competence.

But I’m not going to dwell too much on that right now.

Transforming a bunch of lines drawn by some marine architect (in this case the pleasant and patient Paul Gartside) into a three dimensional shape of compound curves out of wood isn’t some mysterious art.

It’s just a series of processes.

What I’m into now is getting the shape – the real carpentry comes later.

I took that giant graph on the shop floor, measured points out from a centre line for each mold, drove nails in each mark, ran a batten around the curve and marked a line.

This gives the shape of the hull perpendicular to the keel at a particular point to make one mold (there are 12 on this boat).

To transfer this shape to wood I layed nails with their heads resting along that curved line and tapped them gently into the floor so they would stay put.

Now most builders I see on the internet lay a sheet of plywood on top of those nails, then dance upon it to get an indented carbon copy of the shape on the floor.

But I wasn’t going to buy 12 sheets of plywood at $80 a piece.

So, as will be the case with most of this project, I did it the old way because I’m cheap.

Instead I used some of that spruce plank (free!) which had to be cut and fitted together to cover the curve, danced upon it and then subtracted the thickness of the plank to come (an inch and an eighth) using a compass.

Then it was a matter of driving nails in those marks, running a batten again, drawing a line and cutting it out.

A time consuming process that had to be repeated for each of the molds.

Ultimately all these molds will end up in the stove as they get replaced by much more graceful ribs that when done right bring to mind the bones of a bird.

It’s a process as old as boats drawn on paper – of taking someone else’s dream of a shape to cross uncertain water and making it real.

A process repeated in countless barns by countless hands for millenia.

Of course, now they’re 3D printing boats drawn up by someone staring at a screen.

And that’s likely the sad future of it all.

Adding insult to injury, they’re likely far superior craft to the one taking shape in my shop.

But we’ll keep that between us because I’ll never admit it to the owner of plastic boat. If I’m going to throw money into a hole in the water, it’ll be a hole made of wood.

And just maybe, as in life, it’s the journey that matters. On that leap, I’m content to grumble, curse and dream over lines on the floor.

Now it’s a break from the boat to make Christmas presents and then a keel to lay in the new year.

These will all end up in the stove after being replaced by much more lovely ribs made of cold-molded black locust.